NEW SPANISH-LANGUAGE PUBLICATIONS IN UNED RESEARCH JOURNAL

Introduction: The Talamanca Range in the southeast of Costa Rica is a priority region for conservation, but its ecosystems and species are little known. The study of wild mammals can contribute to our understanding of the trophic structure and conservation needs of tropical forests, which are some of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet. Objective: To evaluate the species richness, relative abundance and activity patterns of medium and large mammals in La Amistad National Park and the Quetzal Tres Colinas Biological Corridor. Methods: Continuous monitoring was carried out from July 12, 2018 to April 18, 2021 using 18 photo-trapping stations, each consisting of a camera trap and a scent station. Results: Based on a sampling effort of 15 335 camera trap days, we obtained 36 667 records in which we detected 27 species of medium and large wild mammals, all of which are in one of the risk categories at the national or international level. The species with the widest distribution and the greatest relative abundance were Sciurus granatensis, Tapirus bairdii, Sylvilagus dicei and Mazama temama. The least abundant species, with the most restricted distribution, were Ateles geoffroyi, Cebus imitator and Microsciurus alfari. Five species were diurnal, six were nocturnal and crepuscular, and 14 species were cathemeral. The greatest species richness was found in the Premontane and Lower Montane zones, while the endemic species were in both of these zones and the Subalpine zone. Eight species had lunarphobia, six lunarphilia and six had no pattern. Conclusion: These areas protect important Premontane to Subalpine populations of medium-size and large terrestrial mammals, many cathemeral or with lunarphobia, and should continue to be monitored.

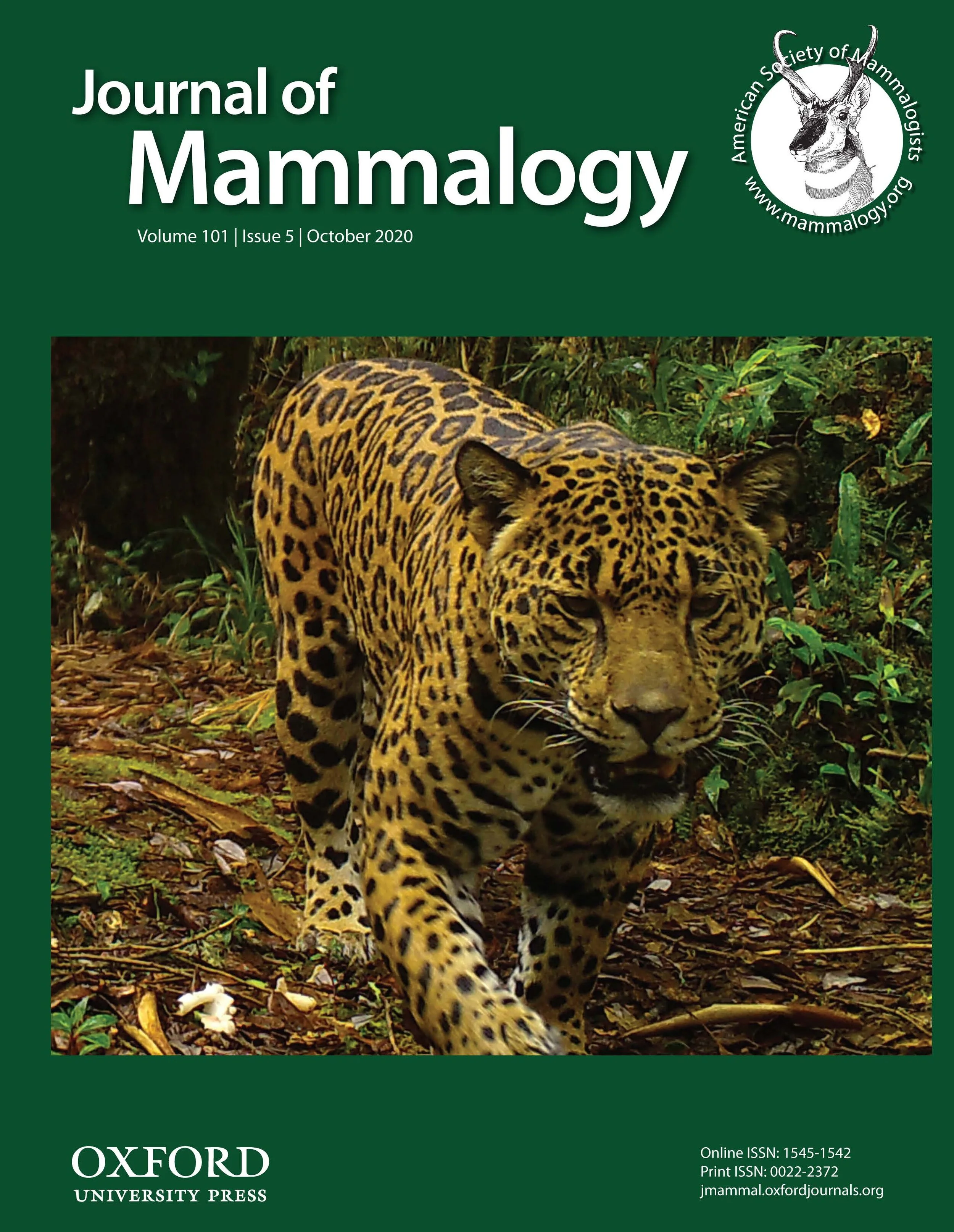

Introduction: The persistence of coat color polymorphisms, such as the coexistence of the melanistic coat color (black) and "wild type" (spotted), is an evolutionary enigma. Objective: The predictions of Gloger's Rule and the Temporal Segregation hypothesis were tested, which propose that melanistic individuals (a) will occur more frequently in dense tropical forest than in open habitat due to the advantages of camouflage and thermoregulation, and (b) will be most active during the brightest times of the circadian and lunar cycle because black pigmentation is cryptic under bright light. Methods: Based on 10 years of jaguar and oncilla camera trap records from dense tropical forest in Costa Rica, the activity patterns and relative abundance of non-melanistic (rosetted or spotted) versus melanistic morphs was compared. Results: Twenty-five percent of jaguar records in dense forests were melanistic compared to the global average of 10% in open and closed habitats; 32% of oncilla records were melanistic compared to 18% overall in Brazil. Overlap analysis indicated that melanistic jaguars were more active during daylight hours compared to non-melanistic jaguars, which were more nocturnal and crepuscular. Likewise, melanistic oncilla were more diurnal than non-melanistic oncilla; melanistic oncilla were also more active during the full moon, while the non-melanistic oncilla were less active. Conclusion: These results imply that melanistic jaguar and oncilla enjoy the adaptive benefits of superior camouflage when inhabiting dense forest and accumulate a fitness advantage when hunting in brighter light conditions. If true, natural selection would ensure that melanistic individuals persist when dense forest is retained but may be threatened by deforestation and accelerating human presence.

Introduction: Temporal niche changes can shape predator-prey interactions by allowing prey to evade predators, improve feeding efficiency, and reduce competition among predators. In addition to circadian activity patterns, the monthly lunar cycle can influence the nocturnal activity of mammals. Objective: Through camera trap surveys at sites on the Pacific slope and the Talamanca Cordillera, we investigated the patterns of circadian (day and night) and nocturnal activity during the moon phases of the jaguar (Panthera onca) and puma (Puma concolor). Methods: We investigated the overlap and temporal segregation between pairs of each predator and its primary prey, and between its competitors using overlap analysis, circular statistics, and relative abundance, taking into account differences in habitat, seasons, and human impact between sites. Results: Our results supported the existence of a temporal niche separation between the two predator species, although both were classified as cathemeral - the jaguar was mainly diurnal, while the puma was mainly nocturnal. We found that the jaguar and puma practice different patterns of nocturnal activity during the phases of the moon, with the jaguar exhibiting a dramatic increase in activity during the full moon and the puma maintaining a more consistent level of activity throughout the moon phases. However, during the full moon, both species were more active at night and less active during the day, suggesting that they practice a temporary niche change to take advantage of hunting activities during the brightest lunar illumination of each month. We discuss predicted primary prey and competing species. Conclusion: We conclude that jaguar and puma exhibit significant niche separation in circadian and lunar activity patterns. Through these differences in temporal activity, jaguar and puma can exploit a slightly different prey base despite their similar large size.

RECENT COSTA RICA PUBLICATIONS!

Temporal niche shifts can shape predator–prey interactions by enabling predator avoidance, enhancing feeding success, and reducing competition among predators. Using a community-based conservation approach, we investigated temporal niche partitioning of mammalian predators and prey across 12 long-term camera trap surveys in the Pacific slope and Talamanca Cordillera of Costa Rica. Temporal overlap and segregation were investigated between predator–prey and predator–predator pairs using overlap analysis, circular statistics, and relative abundance after accounting for differences in habitat, season, and human impact among sites. We made the assumption that predators select abundant prey and adjust their activity to maximize their temporal overlap, thus we predicted that abundant prey with high overlap would be preferred prey species for that predator. We also predicted that similar-sized pairs of predator species with the greatest potential for competitive interactions would have the highest temporal segregation. Our results supported the existence of temporal niche separation among the eight species of predators—the smaller Leopardus felids (ocelot, margay, oncilla) were primarily nocturnal, the largest felids (jaguar and puma) and coyote were cathemeral, and the smaller jaguarundi and tayra were mostly diurnal. Most prey species (67%) were primarily nocturnal versus diurnal or cathemeral (33%). Hierarchical clustering identified relationships among species with the most similar activity patterns. We discuss the primary prey and competitor species predicted for each of the eight predators. Contrary to our prediction, the activity pattern of similar-sized intraguild competitors overlapped more than dissimilar-sized competitors, suggesting that similar-sized predators are hunting the same prey at the same time. From this we conclude that prey availability is more important than competition in determining circadian activity patterns of Neotropical predators. Our results indicate the presence of a delicate balance of tropical food webs that may be disrupted by overhunting, leading to a depauperate community consisting of ubiquitous generalists and endangered specialists. With Central America a hotspot for hunting-induced “empty forests,” community-based conservation approaches may offer the best road to reduce illegal hunting and maintain the biodiversity and community structure of tropical forest systems.

An increasing body of evidence indicates that moonlight influences the nocturnal activity patterns of tropical mammals, both predators and prey. One explanation is that brighter moonlight is associated with increased risk of predation (Predation Risk hypothesis), but it has also been proposed that nocturnal activity may be influenced by the sensory ecology of a species, with species that rely on visual detection of food and danger predicted to increase their activity during bright moonlight, while species relying on non-visual senses should decrease activity (Visual Acuity hypothesis). Lack of an objective measure of “visual acuity” has made this second hypothesis difficult to test, therefore we employed a novel approach to better understand the role of lunar illumination in driving activity patterns by using the tapetum lucidum as a proxy for “night vision” acuity. To test the alternative predictions, we analyzed a large dataset from our long-term camera trap study in Costa Rica using activity overlap, relative abundance, and circular statistical techniques. Mixed models explored the influence of illumination factors (moonrise/set, cloud cover, season) and night vision acuity (tapetum type) on nocturnal and lunar phase-related activity patterns. Our results support the underlying assumptions of the predation risk and visual acuity models, but indicate that neither can fully predict lunar-related activity patterns. With diurnal human “super predators” forcing a global increase in activity during the night by mammals, our findings can contribute to a better understanding of nocturnal activity patterns and the development of conservation approaches to mitigate forced temporal niche shifts.

Mooring, M. S., Eppert, A. A., and Botts, R. T. Natural selection of melanism in Costa Rican jaguar and oncilla: a test of Gloger’s Rule and the temporal segregation hypothesis. (2020). Tropical Conservation Science 13: 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082920910364

The persistence of coat color polymorphisms—such as the coexistence of melanistic and “wild-type” coat color—is an ongoing evolutionary puzzle. We tested the predictions of Gloger’s rule and the Temporal Segregation hypothesis that propose that melanistic individuals will (a) occur more frequently in closed tropical forest versus open habitat due to camouflage and thermoregulation advantages and (b) be more active during brighter times of the circadian and lunar cycle because black pigmentation is cryptic under bright illumination. Based on 10 years of camera trap records of jaguar and oncilla from dense tropical forest in Costa Rica, we compared activity and relative abundance of non-melanistic wild-type morphs (rosetted or spotted) versus melanistic morphs. Twenty-five percent of jaguar records in dense forest were melanistic compared with the global average of 10% in both open and closed habitats; 32% of oncilla records were melanistic compared with 18% overall in Brazil. Overlap analysis indicated that melanistic jaguars were more active during daylight hours compared with non-melanistic jaguars, which were more nocturnal and crepuscular. Likewise, melanistic oncillas were significantly more diurnal than non-melanistic oncillas; melanistic oncillas were also more active during full moon, while non-melanistic oncillas were less active. These results imply that melanistic jaguar and oncilla enjoy the adaptive benefits of superior camouflage when inhabiting dense forest and accrue a fitness advantage when hunting during conditions of brighter illumination. If true, natural selection would ensure that melanistic individuals persist when dense forest is retained but may be threatened by deforestation and accelerating human presence.

NEW BISON PUBLICATION

Abstract - In most polygynous species, males compete for access to females using agonistic interactions to establish dominance hierarchies. Typically, larger and stronger males become more dominant and thus gain higher mating and reproductive success over subordinate males. However, there is an inherent trade-off between time and energy invested in dominance interactions versus courtship and mating activities. Individuals may overcome this trade-off by selectively engaging in more effective mating tactics. North American bison (Bison bison) are a species of conservation concern that exhibit female-defense polygyny with two predominant mating tactics: (1) tending individual females; or (2) challenging tending males as a satellite and then mating opportunistically. Here, we use social network analysis to examine the relationship between position in the agonistic interaction network of bison males and their mating, reproductive success, and reproductive tactics and effort. To assess the potential for social network analysis to generate new insights, we compare male (node) centrality in the interaction network with traditional David’s score and Elo-rating dominance rankings. Local and global node centrality and dominance rankings were positively associated with prime-aged, heavy males with the most mating success and offspring sired. These males invested more effort in the “tending” tactic versus the “satellite” tactic, and they tended more females for longer periods during peak rut, when most females were receptive. By engaging in the most effective mating tactic, dominant males may mitigate the trade-off between allocating time and energy to agonistic interactions that establish dominance, versus courtship and mating. While less dominant males participated more in the alternative mating tactic, network analysis demonstrated that they were still important to the interaction network on both a local and global scale.

Video Recap of our Costa Rica research season 2019!

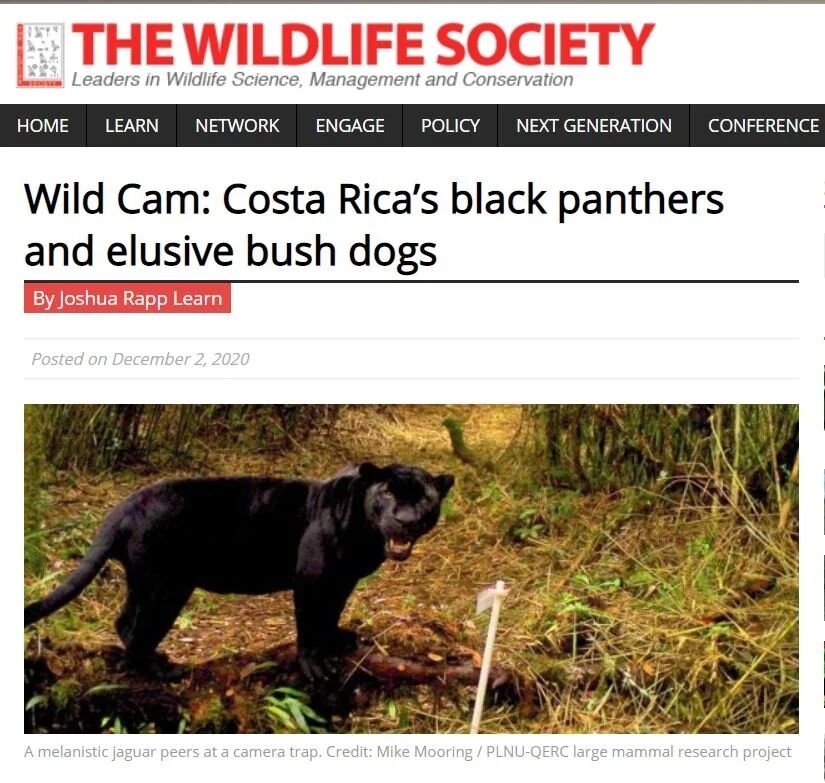

WILD CAM article in THE WILDLIFE SOCIETY online highlights our research with melanistic felids and bush dogs!

Wild Cam: Costa Rica’s black panthers and elusive bush dogs

TALAMANCA LARGE MAMMAL RESEARCH REPORT 2019 – ACLAP

Prepared July 2019

Dr. Mike Mooring

Department of Biology, Point Loma Nazarene University, San Diego, CA 92106 USA

Quetzal Education and Research Center (QERC), San Gerardo de Dota, Costa Rica

Email: mmooring@pointloma.edu

Research Permit: R-SINAC-PNI-ACLAP-028-2019

Entrance Fee Waiver: RESOLUCIÓN SINAC-ACLA-P-D-254-2019

Collection Permit: R-SINAC-PNI-ACLAP-054-2018; No M-PC-SINAC-PNI-ACLAP-060-2018

PILA Trek – June 17-25

10 days (8 on trail), 90 kilometers

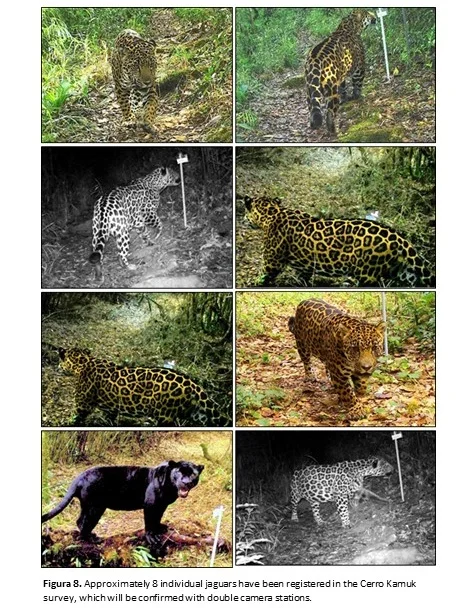

In 2018, we deployed 10 cameras on the Cerro Kamuk trail as part of a collaborative effort between QERC and PILA. During the trek we observed a great many large scats that appeared to be jaguar or puma, many of which were filled with porcupine quills. As we reviewed the photos coming in from the Kamuk camera survey in the subsequent months, we realized that this area is occupied by an unusually high density of felids, especially jaguar and puma. We determined to return in 2019 to collect as much of the felid scat as possible for analysis of the population genetics and diet of these cats.

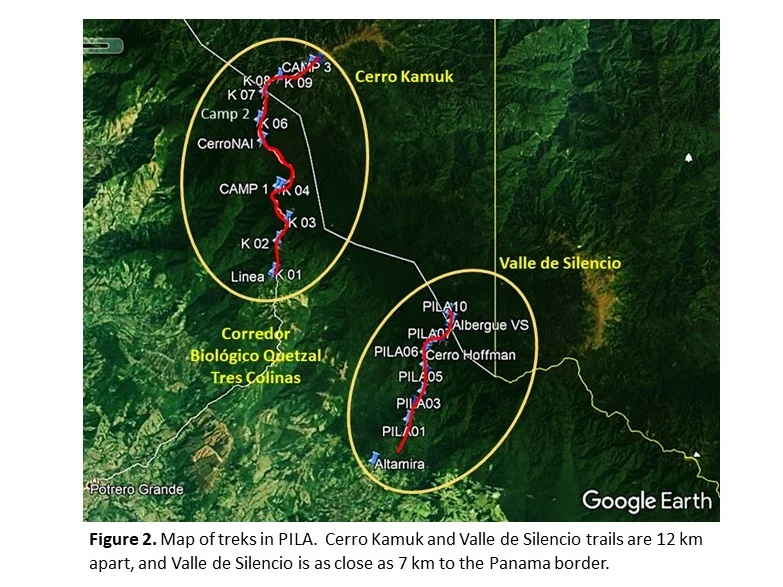

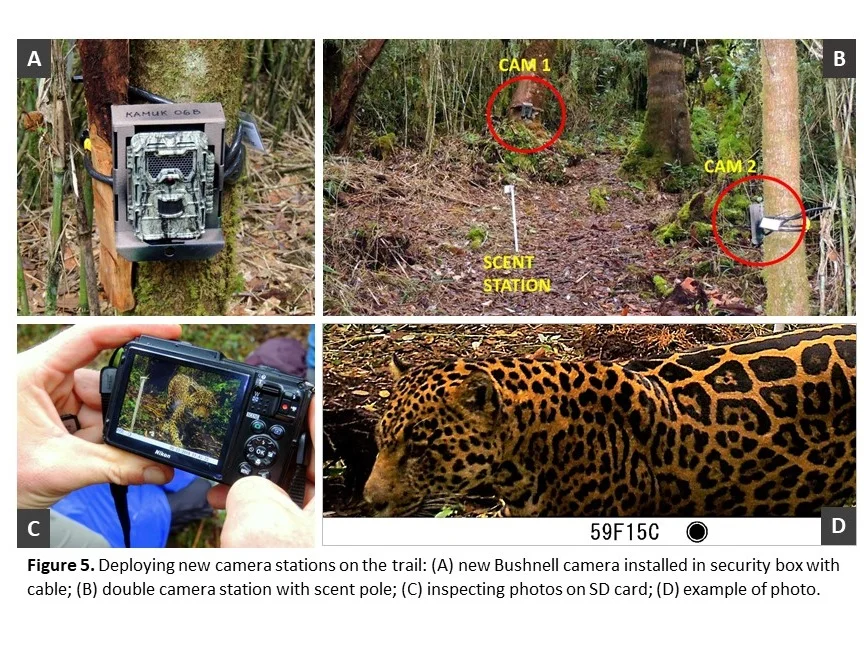

The team consisted of my 4 students and myself from QERC and Point Loma Nazarene University (Steven Blankenship, Amy Eppert, Abigail Wagner, Sierra Ullrich), Tigre the scent detection dog from Panthera with trainer Stephanny Arroyo-Arce and assistant Ian Thomson, and our guide Roger Gonzalez, administrator of La Amistad International Park (Fig. 1). The eight of us trekked the entire 55 km roundtrip length of the trail (Fig. 2); we were joined for the first day’s journey by Fredy Quirós and Yendry Rojas of the Quetzal Biological Corridor and ASOTUR (Asociación de Turismo Tres Colinas de Potrero Grande). We started from Tres Colinas, where we were hosted by Fredy and Yendry in their AirBNB cabina and served a delicious casado dinner, plus breakfast and lunch the next day. We headed out on the trail at 6:00 AM on Monday with 50-lb+ packs on our backs, inching our way up the very steep slopes of cattle pastures until we reached the park limit, then entered montane oak forest and crested Cerro Kwakwa. Tigre was in working mode, with his orange ‘Panthera - Working Dogs for Conservation’ vest on, excited sniffing the trail and travelling back and forth many times over the distance we travelled (Fig. 3-4). Along the way, we also added a second camera to 4 of the stations where we have recorded jaguar in order to improve our ability to identify individuals from their rosette patterns (Fig. 5). We reached Camp 1 after kilometer 10 around 3:00 PM and rested for the rest of the day, eating our staple of strong coffee made in a “coffee sock” and mac ‘n’ cheese with sausage for dinner. Our tents were set up under the black plastic tarps that are erected at the site, with fresh water available from the stream and covered toilet further away (Fig. 6). By 6:00 PM the darkness was falling and we were all in our tents for 11 hours of well-earned sleep!

On Tuesday, we said goodbye to Fredy and Yendry and continued up the trail as they returned down to Tres Colinas. Now the trail traversed up and down innumerable cerros with indigenous Bribri names like Cerro Dudu and Cerro Nai, alternating between montane forest trees covered with hanging moss and boggy tubera habitat with fantastic views of the surrounding mountains. Tigre had a good day of scat detection, finding many of the feline samples that we had come to collect for genetic analysis. Tigre was first primed by Stephanny by use of a felid scat exemplar, and once primed did not stop energetically bounding up and down the trail all day long. Once Tigre discovered an appropriate scat sample, he would ‘mark’ by sitting down and receive his reward, play time with his bright red ball that he is crazy about (Fig. 3). Although Tigre is trained on all six species of wild felids found in Costa Rica, he will not mark for any other predator species such as coyotes. Some of the samples that Tigre marked were too old to be viable for the expensive genetic analysis and were not collected, but each day Stephanny and Ian collected many samples, taking down location coordinates and other vital data with the sample (Fig. 4). Although day 2 involved a lot of uphill climbing, there was enough downhill to add variety and the scenic views kept us in good spirits. We finished the second day at Camp 2 just past kilometer 18 (Fig. 6), adding to our normal routine a rousing bath in the ice cold waters of the adjacent stream – screams of joy (or perhaps shock) could be heard throughout the camp as each of us took our turn bathing at the “swimming hole”!

Day 3 brought us out of the montane oak forest and into the high elevation paramo, a tree-less landscape dominated by Chusquea bamboo and the strange shapes of the other alpine vegetation. As we alternately ascended and descended the trail, passing through tubera and paramo, we were glad to be wearing our calf-high rubber boots that kept our feet from sinking into the deep mud that much of the trail passed through. From time to time we encountered the distinctive three-toed tracks of the many tapirs that are abundant at these elevations, sometimes combined with a tapir latrine piled high with horse-like poop balls. After three days of clear weather, we finally got rainfall in the afternoon that greeted our arrival at Camp 3. Fortunately, Roger at arrived first (speeding along the trail in front of us) and had already erected the plastic tarps that are only temporarily raised in the windy paramo landscape just under the shadow of Cerro Kamuk. Having already hiked 25 km up and down rugged terrain with 50-lb packs, we were glad to flop down, eat our food, and fall asleep in our tents.

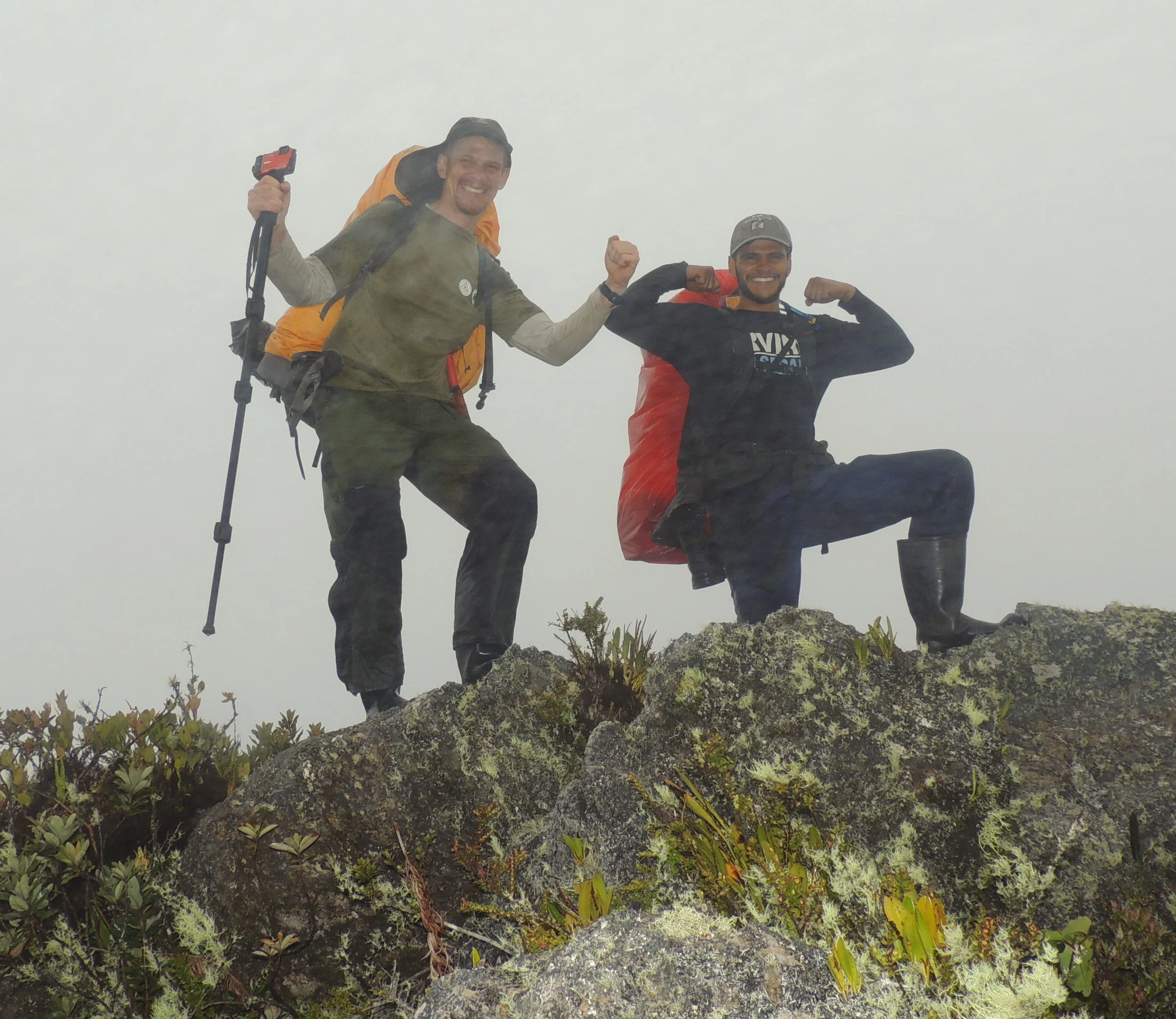

The rain continued through the night and into the morning, but had relinquished by mid-morning when we departed in the fog for the summit of Cerro Kamuk 2.5 km away. With little or no weight on our backs, the climb to the summit was a relief apart from the thin air and we spent about a half hour on the summit taking photos, writing in the log book, and basking in the triumph (Fig. 7). Roger, who had wheeled his bright yellow measuring wheel along the entire length of the trail to mark the kilometers, finally was able to fold up the wheel having measured the entire trail from beginning to end. Because Tigre gets a rest after 3 days on the trail, we spent the rest of the day in camp resting and eating. The return trip took us 2 days as we did 20 km on the last day, returning dead tired to Tres Colinas. Fortunately, we were able to bathe and have a hot meal at Fred and Yendry’s before driving to the Altamira ranger station.

After a day of rest and recovery at Altamira, the team hit the Valle de Silencio trail with Junior Porras, the PILA science officer, as our guide. Although fewer samples were discovered by Tigre (and collected), we wanted to take advantage of the many jaguar photos recorded by the camera stations on this trail, though not as many as recorded on the Cerro Kamuk Trail. The first day was a continuous uphill climb of 15 km, the last few kilometers of which involved clambering over fallen trees. But this time we had a cabina at the end and no need to bring tents along, although we had all our cooking stoves and other camping gear. Along the way we were able to add second cameras to the stations where jaguar had been reported, creating a series of “double camera” stations as on Cerro Kamuk in order to have greater certainty in identifying individual jaguar by knowing the rosette patterns on both sides (Fig. 8). We hiked back to Altamira the next day and completed our La Amistad treks. Altogether, the team collected 52 felid scat samples to contribute to the genetic analysis of the felid populations of the Talamancas.

Chirripo Trek – July 8-12

6 days (5 on trail), 60 kilometers

In 2016-2017, our research team worked effectively with Carlos Orozco of Hablemos de Perros and his scent detection dogs Charlie (2016) and Viper (2017), successfully collecting 64 felid samples that were sent to the UCR Wildlife Genetics Lab for analysis. In 2016, Charlie and the team collected from the San Jeronimo alternative route; in 2017, Viper and team collected from the El Uran alternative route. On the El Uran ridge, we noted a large number of scat samples that we were unable to collect because of pouring rain and we promised to return to collect the remaining samples. Unfortunately, our collection permit was not approved until after the 2018 field season. By then, Panthera had a new scent detection dog, Tigre, under the training of Stephanny Arroyo-Arce, and we determined to return to Chirripo in 2019 to retrace both the El Uran and San Jeronimo routes with our collaborator and guide Enzo Vargas of Chirripo National Park.

Following a 12-day rest and recovery period at QERC, our team and the Panthera Tigre team reassembled at San Gerardo de Rivas for a 5-day trek of Chirripo National Park with Enzo. We started out at 5:00 AM on Monday with a bouncing ride to Herradura to the trailhead of the El Uran alternative route. Similar to the beginning of the Cerro Kamuk trail, the Uran route traversed up through steep cow pastures for the first few kilometers until we entered the park boundary and the cover of montane forest. After a 16 km grueling uphill trudge, we arrived at the “shack”, a corrugated tin shed built by the Herradura community association that operates the guided hikes along this route (Fig. 9). It had rained in the afternoon and we were all wet and tired when we arrived. Before long, dripping wet clothing was hanging from every available nail and hanging spot in the shack. We drank copious amount of strong coffee, filled ourselves with calorie-rich mac ‘n’ cheese with sausage, and grabbed a mattress and prepared a place to spend the night in our sleeping bags. Before it was even dark, we were all in our sleeping bag getting some much-needed rest for our tired muscles. In 2017, we used an outdoor “long drop” latrine we dubbed the “most scenic toilet in the world” for the magnificent view of El Uran afforded when seated as on a royal throne, one side of the structure completely open to the great outdoors. Now, in 2019, improvements had been made, and the toilet was now inside the shack in the basement, and the long drop had been replaced by a flush toilet. There was even a shower, although no one dared to brave the ice cold waters. We appreciated this “luxury”, especially since we did not need to carry as much weight as we had on Cerro Kamuk!

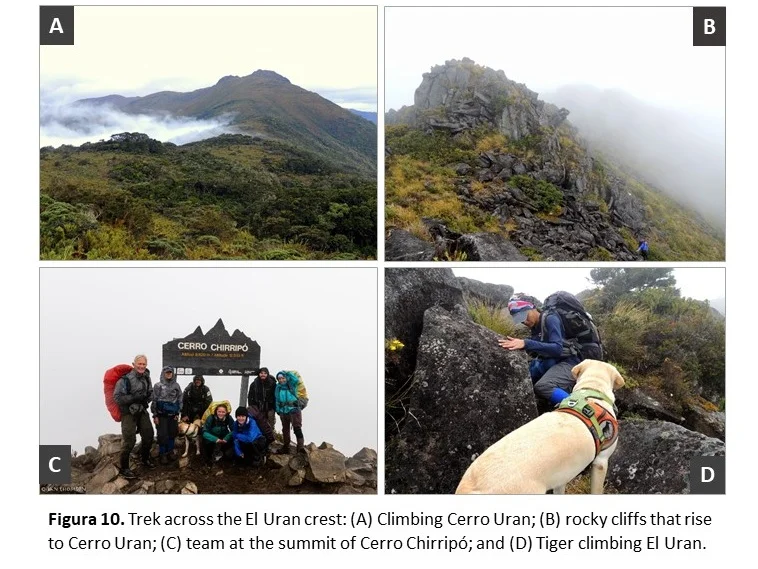

We awoke to the morning of the second day with overcast skies and a cold foggy drizzle in the air. We could see the peak of El Uran in the distance far up as we started out, and little by little we got closer and closer to the peak until we finally reached the massive pile of rock slabs that we had to clamber over (Fig. 10). The majority of the day was spent getting over the El Uran ridge, which is much longer than it appears. Each time that we thought we were getting close to Chirripo we were disappointed to discovered we had reached another “false summit” and were still hours away. The weather shifted from calm to windy to drizzling to raining and then the rain would stop and we would start the cycle again. At many points along the way we had to heave ourselves over massive granite boulders, and Tigre had to be pushed and carried over some of the very steep rocks as well (Fig. 10d). Although we saw a lot of scat along the trail, much of it was too old to collect, some perhaps dating back to our last trek along the El Uran ridge in 2017. We wondered if the heavy traffic of guided hikers along El Uran (which we saw when we check the cameras) could be causing wildlife to avoid the trail? At last, toward the end of the day, in drenching wet and foggy rainfall, we crested the summit of Chirripo, quickly took some photos (Fig. 10c), and headed briskly down the trail to the Base Crestones hostel about an hour away. All of us were too wet and tired to collect any more samples! At Base, we got into dry clothes and had hot coffee and hot food, then settled into our bunkbeds, which were far more comfortable that either the tents of Cerro Kamuk or the floor of the shack!

Because Tigre’s paw needed to heal, Tigre too the next two days to rest and recover from his injury. On Wednesday we had a rest day, which gave us time to wander around the Crestones valley and explore the birds, lizards, and wild flowers. Enzo returned to San Gerardo de Rivas by way of the Main Trail to attend to park business, but would meet us at the end of the San Jeronimo trail. On Thursday, the team set out without Tigre and Stephanny but with Ian to train us in the scat collection technique used by Panthera. All of us took turns in doing the various tasks (Fig. 4): (1) deciding if a scat was worth collecting, for example was it fresh enough?, (2) collecting the sample in a double ziplock bag without touching it to avoid contamination, (3) marking the location on the GPS units, (4) writing down all the details of the collection and the coordinates on a paper slip that was inserted in the collection bag, and (5) sanitizing our hands and packing the sample. Ian carefully observed our performance, giving wise suggestions to avoid problems, and at last pronounced that we were qualified scat collectors. We collected 13 samples that day which we hope are useful even though Tigre did not approve them!

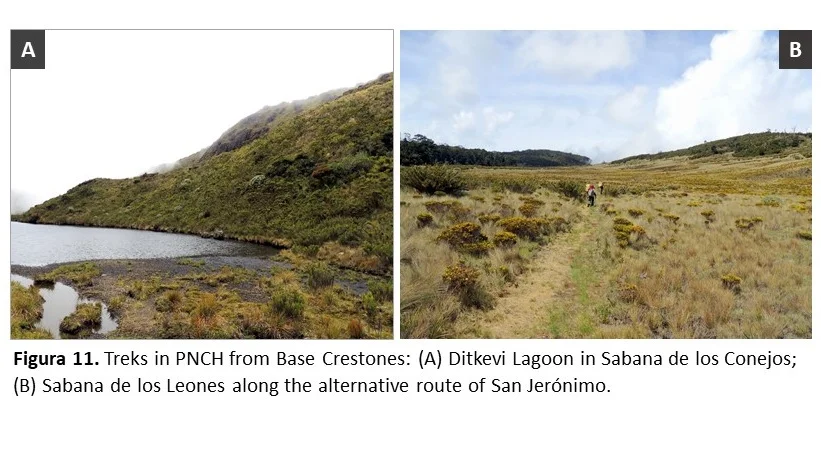

On Friday, our last day of the trek, we packed all our gear and headed down the San Jeronimo alternative route, checking and changing cameras and collecting scat as we went. The sky was clear, the sun was hot, and the trail was long. We were guided by Andres, guardaparque from Base, through Sabana de Leones, a vast high elevation grassland, and into the montane forest before he returned to Crestones (Fig. 11). For the last few hours of the hike we went continuously downhill, eventually arriving at the park boundary in the rain and mud. We gratefully bounced in the back of the truck with Enzo at the wheel for about 2 hours before arriving back at the San Gerardo station. Stephanny awarded the QERC team special Tigre stickers and tee shirts from Panthera. With last smiles and hugs, we piled into the car at returned to QERC that night. Altogether, Tigre and company had collected 29 samples during the 5-day trek in Chirripo (Fig. 12). We were pleased to have collected a record total 81 scat samples during the total of 13 days on the trail and 150 kilometers of hiking!

Congratulations to everyone involved in the treks!

Tigre the wonder dog and Stephanny and Ian

Roger and Junior of PILA

Enzo and Andres of PNCH

Gustavo Gutierrez of UCR Wildlife Genetics Laboratory

NEW PUBLICATION ON BUSH DOGS IN COSTA RICA

Bush dogs (Speothos venaticus) are a small, wide-ranging Neotropical pack-hunting canid whose ecology is relatively poorly known. Here we document new locations of bush dog groups in east-central (Barbilla National Park) and south-eastern (La Amistad International Park) Costa Rica that suggest either that their recent or historic range has been underestimated, or that their potential range in Central America may have recently expanded and could now include not only borderlands with Panama, but perhaps a substantial portion of the Talamanca Mountains up to 120 km to the north-northwest and at elevations up to 2,086 m. Confirming bush dog presence is elusive; even with a camera trapping effort of over 2,500 trap-nights, there is still, on average, a 50% probability of not getting a bush dog photo even though bush dogs are present. This is to be expected in light of their inherently low density, but means that documenting their current and future distribution in Central America will be difficult.

Read the full article: Bush Dogs in Central America: Recent range expansion, cryptic distribution, or both?

A family of rare and elusive bush dogs caught by the camera trap…

July 2018

Cerro Kamuk Trek

Our research team has been heading up a long-term survey of the large mammals inhabiting the Talamanca cloud forest in Costa Rica since 2010. Working with local “Tico” (Costa Rican) collaborators, we have built an extensive network of camera traps (automatic trail cameras) in 7 national parks, 6 private reserves, and 4 biological corridors in the Talamanca Cordillera, the most rugged and least studied mountain system in the country. We want to understand the population status of the many endemic and threatened mammals that live there, especially the 6 species of wild felids (jaguar, puma, ocelot, jaguarundi, margay, and oncilla) and their prey, including the endangered Baird’s tapir. Our goal is to come alongside Tico conservationists to empower them to conduct their own research and promote community-based conservation. We believe this is a truly holistic and Biblical approach to caring for the magnificent biodiversity of God’s creation and building hope for the future.

The 2018 research team (Fig. 1) consisted of a computational and analysis team (everyone, with Ryan Botts, TJ Wiegman, and Amy Eppert taking the lead) for the first 5 weeks, and a Costa Rica field team (Mike Mooring, Abner Rodriguez, Amy Eppert, and Steven Blankenship) for the last 5 weeks, with TJ continuing the computational work on campus. From May 21-June 22, Amy apprenticed to TJ to write scripts using the ‘R’ programming language and the ‘Shiny’ interactive web app to analyze our huge camera trap database of circadian and lunar activity patterns and overlap of activity budgets between predator and prey species. Meanwhile, Steven apprenticed to Abner to review publications and write the draft introduction and methods for two proposed publications based on the activity analyses. TJ also improved the ‘Shiny’ activity overlap tool to specify actual time of sunrise and sunset (for cataloguing nocturnal vs. diurnal activity) and to research the occupancy analysis that will be the next phase of our computational activities.

The field team departed for Costa Rica on June 23 and returned on July 26 having successfully completed our ninth year of research in the cloud forests of this amazing country. We were based at SNU’s Quetzal Center (QERC) in San Gerardo de Dota, a small mountain community under the shadow of Cerro de la Muerte, the second-highest peak in Costa Rica. This year, our research season overlapped that of Dr. David Hoekman (SNU) and his “Insect Team” and the Hoekman family, and we shared meals, journal article discussions, devotionals, and evening game times with our enlarged QERC family.

This year, our team was able to successfully complete an ambitious project in La Amistad International Park (PILA) that involved the enlargement of our local camera trap survey from 5 cameras to 25 cameras in remote locations. PILA is the largest park in Central America and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, consisting of 400,000 ha (4000 km2) of rugged mountain terrain in Costa Rica and Panama. Home to three indigenous tribal groups, PILA represents a major biodiversity resource – but the mammal fauna is not well known. In 2017, we worked with Roger Gonzalez (PILA Administrator) and Junior Porras (Research Officer) to collect felid scat for genetic analysis and to deploy 5 camera traps on the Valle de Silencio (“Valley of Silence”) trail. In front of each camera, we erected a scent pole to attract passing animals to obtain better photos (the scent is Calvin Klein’s ‘Obsession’). We soon discovered that the cameras were a gold mine of biodiversity information, with at least three individual jaguars making a regular appearance on the cameras, along with puma, ocelot, and margay, and prey species such as paca, peccary, and Baird’s tapir. In fact, it was one of these cameras that produced the first photos of bush dog (a rare, puppy-like canid) documented in the Costa Rican side of PILA. Due to the success of our small array of cameras, we decided to enlarge our camera trap survey efforts in 2018.

(L-R) Abner Rodriguez, Steven Blankenship, and Amy Eppert eat a well-earned dinner of Mac 'n' Cheese with salchichon (sausage) at Valle de Silencio.

On July 9-10, our team (Fig. 2) joined Junior Porras and 3 student volunteers from the National University (UNA) to hike the trail from the Altamira park station to the primitive hostel in Valle Silencio and return the next day. Our goal was to erect 5 new cameras and scent stations on the upper reach of the trail on the Caribbean side of Cerro Hoffman. The trail is very steep and long, 15 km each way, and we hiked in the rain on the second day. The hostel at Valle de Silencio was primitive but we had running cold water, a gas stove, and bunkbeds with mattresses – what luxury! Our trek was successful in deploying the new cameras and proved to be a good training hike for our next adventure.

After a day to recover, we left Altamira station early on the morning of July 12 for the small community of Tres Colinas where we would start our 5-day trek to Cerro Kamuk and back, returning on July 16. Roger Gonzalez was our guide, having hiked the trail many times before and with an intricate knowledge of the logistics and biology along the way. The trail to Cerro Kamuk is rugged and very muddy during the wet season, with a steep initial ascent to the park boundary and then a never-ending series of ascents and descents from one peak to another and another: Cerro Kutsi, Cerro Bekom, Cerro Kasir, Cerro Nai, Cerro Dudu, Cerro Apri, and finally Cerro Kamuk. Cerro may be translated as “Mount” and the mountain names are in the indigenous Bribri language – for example, Cerro Nai is “Mount Tapir”, Cerro Dudu is “Mount Bird”, and Cerro Kamuk is “Place of Rest”. Unlike most Costa Rican national parks, there are no services on this trail other than 3 primitive camps that have been set up along the way at one-day intervals. Each camp has a black plastic tarp erected on the trees as protection against the rain, a nearby stream for drinking water and bathing, and a simple toilet consisting of not much more than a hole in the ground. Everything we needed had to be carried in the packs on our backs: tents, sleeping bags, food, stove, and dry clothes in addition to the 10 cameras and associated gear (boxes, cables, scent poles). Each of us had 45-50 lbs of weight to carry up and down steep slippery trails for the 5 days, although they did became a bit lighter as we erected cameras.

Initially, we trekked through oak montane forest, the trees covered with hanging moss and epiphytes (plants that grow on trees). After the first day, the forest shifted to cloud forest dominated by epiphytic bromeliads, rosette-shaped aerial relatives of pineapples that make up to 25% of the cloud forest biomass. As we climbed higher, the cloud forest periodically merged into the humid transition zone called “turbera” (literally “peat bog”) dominated by sphagnum moss, and later broke into “paramo” habitat on the peaks above treeline. Paramo is essentially the tropical version of the alpine zone, a high elevation habitat dominated by Chusquea bamboo and other brushy vegetation. The view from the paramo was always spectacular, although limited by the ever-present mist and clouds.

One of the 10 camera stations deployed on the Cerro Kamuk trek.

Once past the official park boundary, we positioned a camera station about every 2 kilometers. We aimed to place each camera station along a straight stretch of trail in which animals would be in view of the camera for a longer time, with a tree of the correct width to attach the camera box with a cable (not too large or too small). The positioning of the camera was tested by using a team member to act as the “jaguar”, and then the camera was positioned at the correct angle and activated. We attached a placard to each camera and scent station saying “mammal research, please do not disturb” and recorded the coordinates and elevation with our GPS units. Later we would download these data and create maps of the camera locations.

For lunch, we ate tortillas with bologna and Costa Rican queso duro (hard cheese) to keep up our energy. We typically arrived at camp in early afternoon and boiled water for coffee on our camp stove and erected our tents under the plastic tarp; sometimes we even bathed in the ice-cold streams! Our standard dinner for the trip consisted of Mac ‘n’ Cheese with summer sausage, which was nutritious and filling. We typically were in our sleeping bags by nightfall at 6:30 PM and slept until first light at 5:00 AM, acquiring much needed rest to recover from the day’s exertions and renew our energy for the next leg of the journey. Breakfast consisted of granola, oatmeal, and hot chocolate. After packing our gear, we were on the trail by 7:30.

(L-R) Roger Gonzalez and Abner Rodriguez celebrate in the rain and fog as they summit yet another peak on a hard day of hiking.

Day 3 was the hardest day of hiking, with the trail ascending and descending 17 peaks as we hiked along the ridgeline from Cerro Dudu to Cerro Apri. The weather was cold, windy, and interrupted by occasional light rain. The trail was incredibly muddy and steep, taxing our physical strength to the max. The three of us wearing botas de hule (rubber boots) were glad that we could keep our feet relatively dry as we trudged through deep mud, while those with regular boots tried their best to sidestep the deepest mud (often without success). We continued to erect camera stations, although it became harder to find relatively flat stretches of trail with an appropriate tree available on which to mount the camera. Finally, we reached Camp 3 in the paramo above 3300 m, 2 km from Cerro Kamuk. At this camp, the winds are so strong that the plastic tarps must be erected and taken down by each group, and the clouds and fog were so thick that we could not see Cerro Kamuk 2 km away. By now, the team was exhausted and cold so we decided against continuing on to the summit of Kamuk, which would require another 4 hours of hiking up very steep slopes in the fog and rain. Instead, we focused on resting up, preparing hot food and coffee, and settling down to a long night of strong winds and rain. Nonetheless, the scenery was spectacular and throughout the trek the scenery around us was mind-boggling, so wild and pristine. We returned to Tres Colinas two days later, and after changing into clean clothes, we enjoyed a celebration dinner at McDonalds in San Isidro!

Roger and the local community will erect 5 additional cameras in the Quetzal Biological Corridor, and every two months for the next year he will return to hike the trail, monitor the cameras (change batteries and chips), and retrieve the photos. We are confident that the camera trap survey will provide a wealth of new information about the large mammals of PILA and the Cerro Kamuk region. During our 5 days on the trail, we saw continuous signs of tapirs and large felids (jaguar or puma) based on tracks and scat. It is likely that this region holds some of the richest mammalian biodiversity in PILA, and we are very happy to have been able to set up the camera survey. We are grateful to Roger for guiding the trek, and to the Lord for His protection and giving us the breath in our lungs and strength in our legs. There is no question that this project will increase our understanding of the mammalian fauna of La Amistad.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

June 2017

The star of the expedition (L-R): Carlos Orozco of Hablemos de Perros, trainer/handler of Viper, the Belgian Shepherd Malinois and scat detector extraordinaire.

Expeditions to El Uran and PILA

This year our research team conducted two expeditions to collect felid scat as part of a nationwide project to characterize the population genetics of jaguar, puma, and other felids in Costa Rica. Our goal is to increase the representation of fecal samples from the Talamanca Cordillera, which has been under-represented in recent surveys. We again joined forces with Carlos Orozco of Hablemos de Perros to maximize our effectiveness by using a scent detection dog trained to find and mark felid scat. Carlos is renowned as the trainer of Google, Panthera’s famous jaguar scat detection dog. This year we worked with Viper, a Belgian Malinois Shepherd with strong athleticism, great personality, and a powerful nose. Handled by either Carlos (PN Chirripo) or Manuel Orozco (PILA), Viper would go ahead of the team on the trail and mark any felid scat she found by sitting down. Team members Abner Rodriguez and Wyatt Garley then went to work placing the sample in a plastic bag and recording the GPS coordinates and other information. Upon return from the field, the samples were frozen for storage and later delivered to Dr. Gustavo Gutierrez at the Wildlife Genetics Lab at the University of Costa Rica, where the DNA is extracted and genetic microsatellite analysis conducted by Sofia Soto and Otto Monge.

The mists of El Uran, where we found and collected many felid scats (before the rain hit!).

El Uran Ridge, Chirripo National Park (May 15-18): We travelled to the San Gerardo de Rivas ranger station on May 15 where we joined Enzo Vargas and Roberto Delgado of PNCH and spent the night. We made the ascent on the Main Trail and returned via the El Uran trail on May 18. The 3-day, 50 km hike was extremely tough but very productive in terms of scat collection. Our goal was to traverse the remote El Uran ridge accessible via the summit of Mount Chirripo. We climbed to the Base Crestones hostel on day 1, where we stayed the night. Although we had intended to go on to Sabana de los Conejos to collect scat, this was prevented by heavy rain in the afternoon. We rose early on day 2 and climbed to the summit of Mount Chirripo, stopping long enough to take photos and write in the log book. Viper is the first dog to officially summit Chirripo! We then continued along the El Uran ridge with goal of reaching the “shack” by the end of the day. The El Uran trail has been closed for several years and was difficult to follow in spots, but soon Viper started to find a lot of scat and the team was processing the samples as fast as they could. Light drizzle turned into heavy rain and eventually it was too wet for Viper to smell the scat and so we hurried on. The rain never stopped, the trail turned into a river, and several hours later when we arrived at the shack we were cold and soaking wet. A quick change into dry clothes and sleeping bags and the team went to bed at 6 pm. The next day we continued on the trail but little scat was found and we returned to the ranger station with 31 samples, which comes to a total of 64 samples with the scat collected in 2016 on the San Jeronimo trail. Next year we hope to hike the El Uran trail in the opposite direction (west to east) and sample Sabana de los Conejos before returning via the San Jeronimo trail.

Wyatt Garley deploys a camera trap on the Valle de Silencio trail.

Valle de Silencio & Cerro Pittier, PI La Amistad (May 29-June 1): The team travelled to the Altamira ranger station of PILA on May 29 where we joined Junior Porras and administrator Roger Gonzalez. The next day we hiked the Valle de Silencio trail as far as Cerro Hoffman, which is the boundary line between ACLAP (Area Conservacion La Amistand-Pacifico) and ACLAC (La Amistad-Caribe). Because ACLAC does not permit dogs inside their area (even conservation dogs), we had to turn around and go back to Altamira at that point. As we hiked the trail beyond Casa Coca, we deployed 5 new cameras that will continuously record the wildlife travelling on the Valle de Silencio trail. On day 2 we drove from Altamira to the Pittier station and spent the day hiking an old trail to Cerro Pittier that we learned had not been in use for 20 years. The many fallen trees and overgrowth slowed our progress, and eventually we reached a dense bamboo thicket that forced us to turn back. The next day we hiked a short trail and returned to Altamira. Although our scat collection was disappointing (4 samples), the new camera traps made the expedition well worth the effort. The first photos we received had both melanistic (black) and rosetted jaguars that had travelled along the same trail we hiked on the first day. Subsequent photos produced 10 records of 3 individual jaguar plus bush dogs, as reported in the summary (we now have many more records!).